While he is occasionally depicted as doing it for her, she is negated this possibility of making her love for Montalbano explicit by way of her culinary preparations.

In order to prevent her from cooking, Montalbano often suggests taking her out for dinner to his favourite restaurant (Calogero’s) in Vigata, the imaginary Sicilian town where all of his stories are set: their relationship always appears of the oscillating kind, partly and perhaps also because Montalbano ultimately fails to let Livia cook him food, and so feed him. Livia is from Northern Italy (she lives in Genoa, and often visits Montalbano at weekends where she is repeatedly neglected because of the Inspector’s job duties) and is “obviously” depicted as a bad cook, and is praised in the rare occasions when she manages to prepare something vaguely acceptable for Montalbano. This is importantly also symbolical of his own relationship with Livia, his long-term, long-distance girlfriend. Montalbano is not one to eat voraciously, or even frequently: Montalbano takes his time eating, and most importantly he is one of those that he would probably not eat at all if he were to eat bad food.

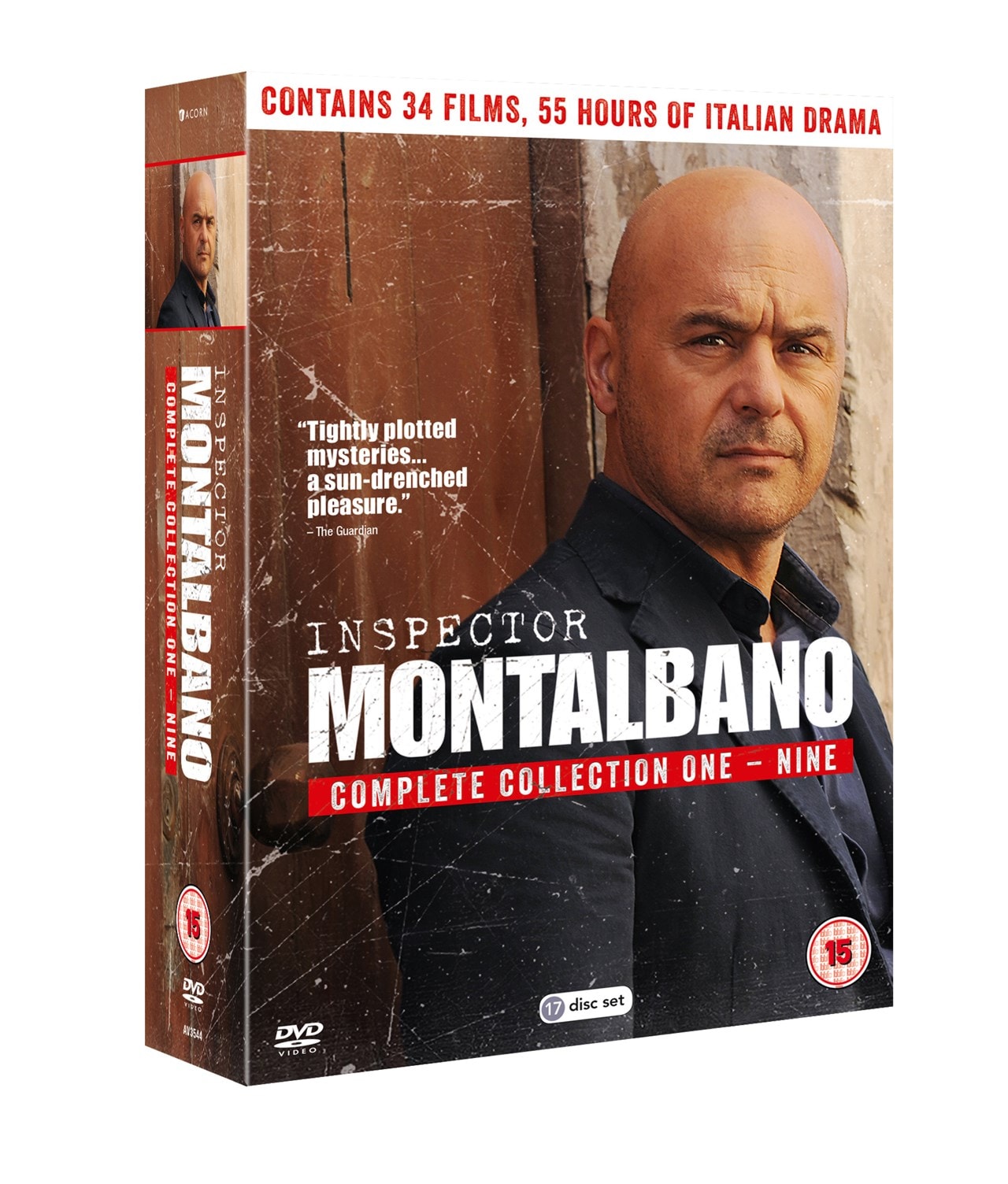

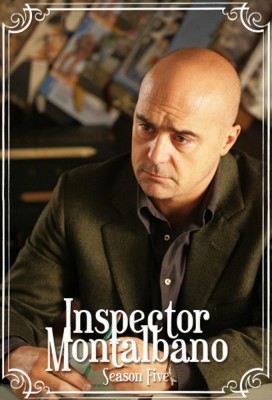

#Inspector montalbano series#

Those of you who are familiar with his novels and collections of short stories, or maybe have watched the series as it was broadcasted on RAI and BBC, will be familiar with Montalbano’s obsession with food. Andrea Camilleri viscerally connects his genial literary creation, Inspector Salvo Montalbano, with food, and most specifically with arancini. At the same time, how could “arancini” (little oranges) be otherwise translated in English? Their name is reminiscent of warm, sun-ripened Sicilian oranges, whilst being in the shape of this fruit, but occasionally of pears too, and their connotation makes most Italians’ mouths water immediately with the crispiness of their deep-fried, breadcrumb coating, the juiciness of their savoury filling (which, indeed, reminds one of blood oranges), and the comforting texture of risotto.Īpparently of legendary Arab and Norman origins, like most original Sicilian food otherwise (remember Joyce’s blancmange/biancomangiare?), arancini are now the most wanted Sicilian street food across Italy. Then again, I find it hard to believe that such a specific Italian word for one type of Sicilian street food could be added to a dictionary of the English language: yet, I remember seeing the local Zizzi’s (a most popular “Italian” restaurant chain in the UK) advertise their new arancini (which, I suspect, I am not going to try soon, as I have made mine own!), and I can imagine they can be occasionally spotted here and there in some Italian restaurants in the UK, although I have not seen them frequently in their menus. This made me smile, of course, because it means Italian can still influence other languages –albeit mainly through food items.

Not long ago, I was informed by a student in an essay that the word ‘arancini’ had made its way into Oxford Dictionaries in 2014.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)